Looking ahead to 2025, Australia’s housing market is set to experience a period of moderation in the short to medium term, primarily driven by decreasing lending power and anaemic wage growth, only offset in the short term by a Supply-Demand mismatch and expectations of future reductions in monetary policy. Compounding these factors together is likely to lead to flat prices over the near term, especially after taking the erosion of inflation into account. Now for the data.

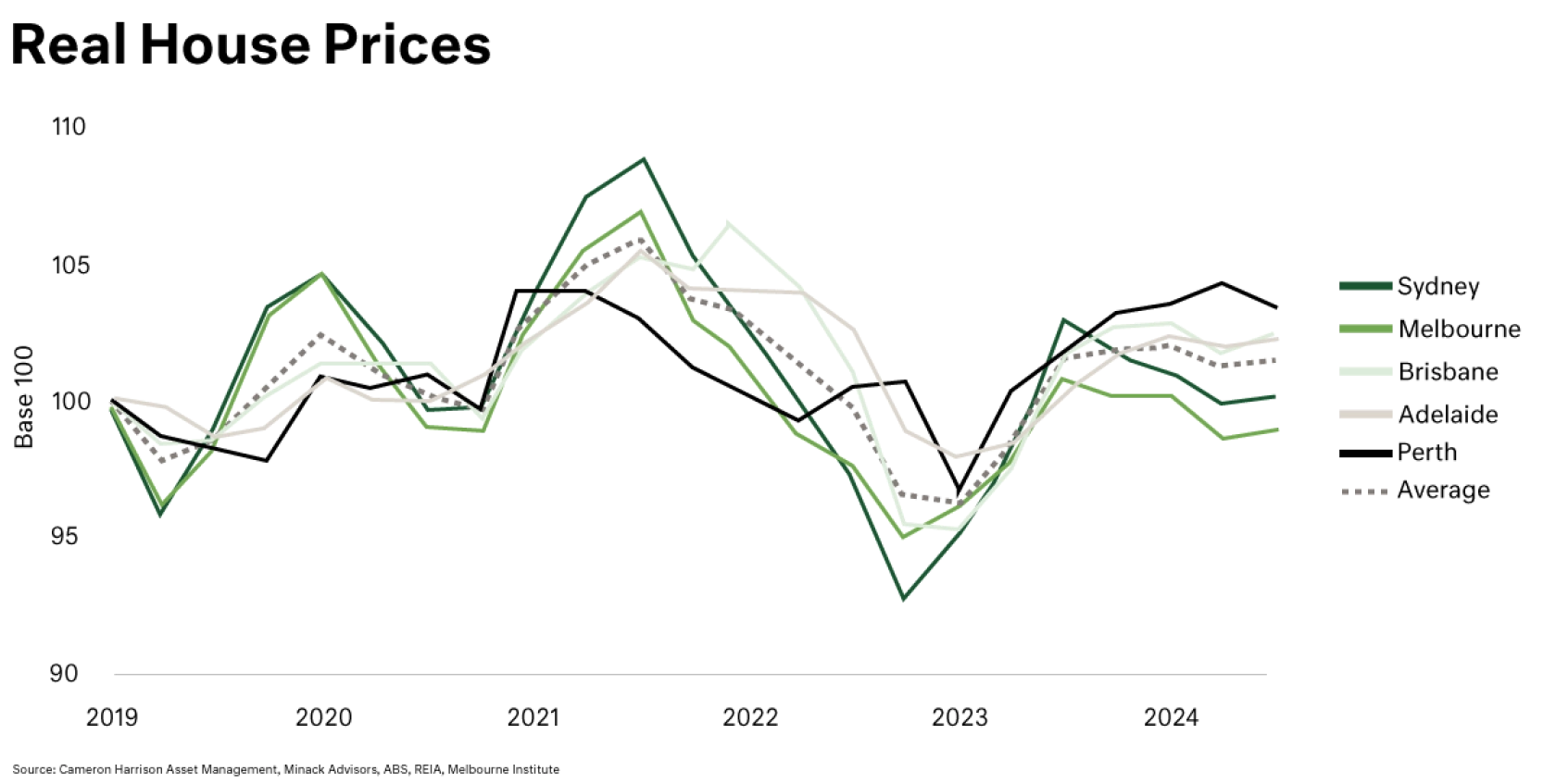

Below is a chart of Real House Prices (based on median prices) since the beginning of 2019. “Real” meaning these figures are adjusted for the erosion in purchasing power caused by inflation:

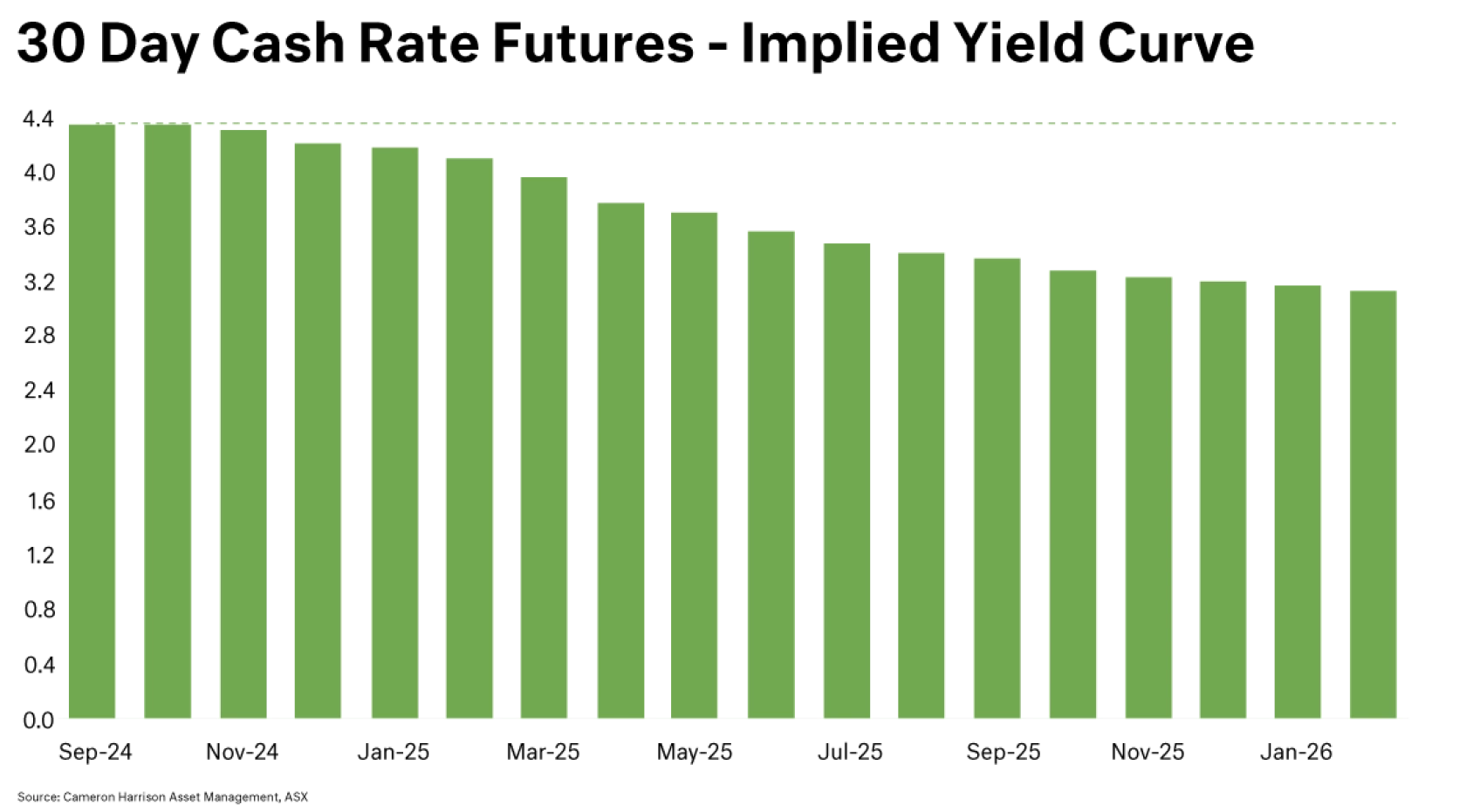

We can see that over the past five years, real property prices have remained relatively flat. These are tabled below for the selected major cities:

So why are prices flat (or negative in Melbourne’s case), and where can we expect prices to be in the future?

The direction and magnitude of house price movement is a function of upward and downward pressures. These are discussed below.

Fiscal Greed & Immigration

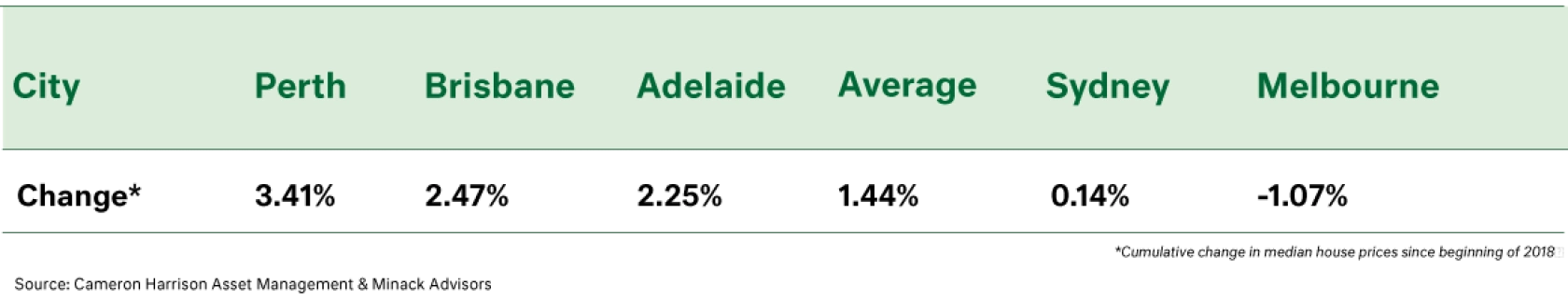

At the most fundamental level, Australia’s current housing dynamics stem from a Supply-Demand mismatch, engineered by fiscal policy (immigration). Governments enjoy having increases in population as this increases the workforce on an aggregate level, leading to higher tax revenues to fund ineffective spending policies. This was apparent in the Federal Government’s recently announced budget surplus for 2023-2024 of $15.8 billion which contained increased individual taxation of $35 billion or 12% from the prior year; due to 1 million new taxpayers and bracket creep. The below chart shows that current levels of immigration are abnormally high compared to the trendline pre-COVID. The annual growth to March 2024 was 615,300 people (2.3%).

The Federal Government’s aggressive immigration policy has created a stark mismatch between housing supply and demand, putting upward pressure on house prices. With record numbers of new arrivals boosting demand for housing, the market faces increasing strain as the supply side remains relatively fixed.

High input costs for construction materials, labour shortages, and lengthy approval processes for new developments delays the creation of additional housing stock. These bottlenecks mean that the housing supply is relatively fixed in the short term, unable to keep pace with the rapid rise in demand caused by more people coming into the country who require accommodation. Further, there is also a significant time cost associated with increasing housing supply; on average, it takes between six and twelve months to construct a new home.

The result is a classic imbalance: as more buyers compete for a limited pool of available homes, prices are pushed higher, exacerbating affordability challenges.

Forward Path of Interest Rates

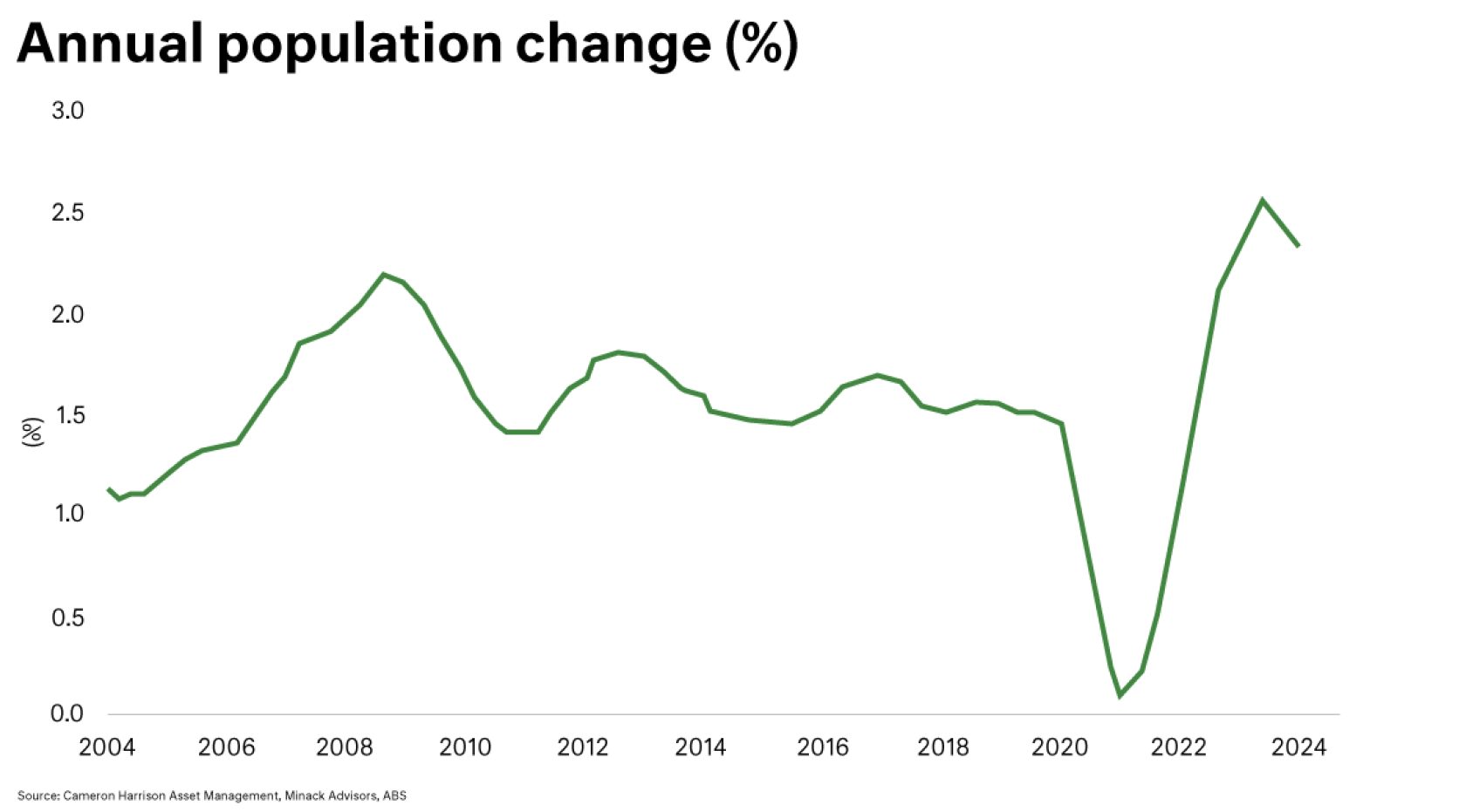

In the broader context, the cash rate is an important factor in determining the future direction of house prices. The cash rate directly flows through to borrowing costs for floating rate debtholders and new mortgagees. As long as this remains expensive (relative to recent history) and household incomes fail to keep pace, a downward pressure on property valuations will likely persist as property becomes less affordable (see our recent Chart of the Month).

However, given market expectations (see below chart) of rate cuts in early 2025, this would act as a rising tide, buoying house prices throughout this period. The theory is that as borrowing costs recede, the allure of property purchases increases, amplifying demand and pushing valuations upward.

Further, lower rates in the near term are expected to increase debt servicing ability for households, insofar as wages are not eroded by inflation, thereby off-setting any ease to (prospective) homeowners.

We view the prospect of lower interest rates in 2025 as having a muted impact on mortgage affordability given rate cuts are not likely to be significant, and embedded higher household costs will remain a ‘drag’ for some time to come. That said, lower rates will invariably provide some boost to confidence. With lower bond rates in Australia supporting capital markets, higher end property values should be underpinned (though growth may be modest). Construction is an underpinning of value, whilst land values a ‘drag’.

Wages and Affordability

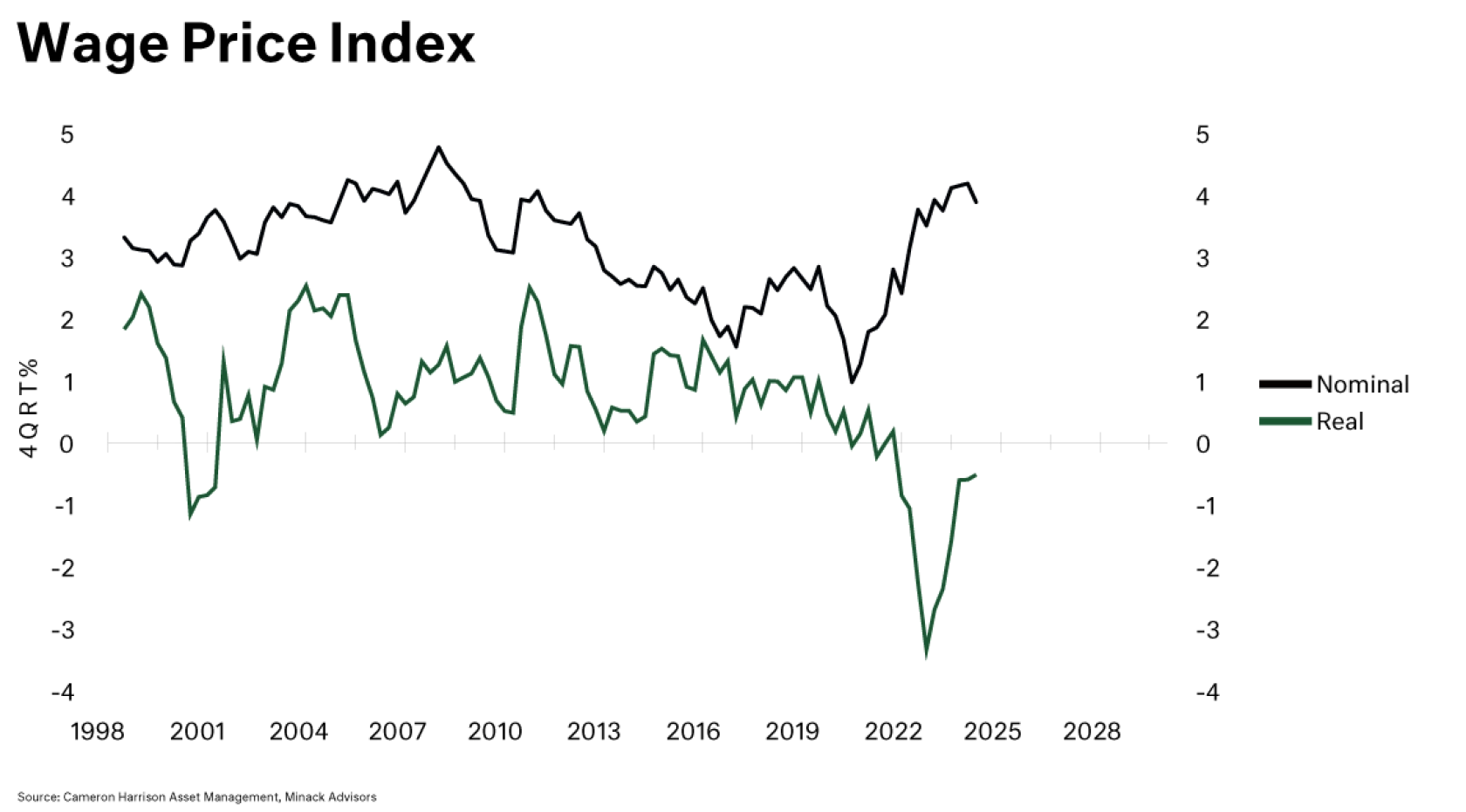

Large inflows of workers from the aforementioned immigration policy causes businesses to have a larger pool of workers to fill jobs from; this moderates wages. Real wages are further dampened by the ‘sticky’ inflation experienced recently, as any annual pay increases have their increased purchasing power eroded away by inflation (and tax ‘bracket-creep’), leading to negative real wage growth (see below chart).

As real wages and income stagnate, the ability of buyers to keep up with rising property prices diminishes, suggesting a cooling force in the market.

Rental Property

The rental market remains very tight, but over the last quarter, we have started to see a reduction in the rate of growth in rents. They are still relatively high (7% p.a. to August 2024), and this trend has continued in September, particularly in Melbourne. Also, we are starting to see a modest improve in rental vacancy rates. This is due to the interaction of price and supply, and there being an absorption of vacant rooms (as opposed to vacant whole properties). Whether it is staying at home longer or group sharing of accommodation, the pricing mechanism of higher rents is causing some improved utilisation of housing stock.

With gross rental yields of 3.7% p.a. and moderating growth in rental rates, the real yield is zero (and negative when accounting for costs and depreciation). Combined with increased State levied land taxes on investment properties, the cashflow equation for rental properties is not strong. Recent commentary on Treasury undertaking a review of negative gearing and the level of CGT discount is unsettling for investors, and likely to add to downward pressure to investment property prices.

Lending Capacity

When purchasing a house with debt in the capital structure (mortgage), lending capacity is typically a function of gross wages (covered previously) multiplied by a “Lending Factor”. This Lending Factor increases in periods of strong economic growth, as banks become more comfortable with their borrower’s ability to pay back debt and tightens in periods of uncertainty. As the forward economic outlook remains shrouded in uncertainty, lenders, wary of higher interest rates and household debt levels, have been scaling back credit availability. APRA also overlays a lending buffer of 3% to prevailing variable rates, which implies a serviceability interest rate of close to 10% p.a. Tightening bank credit is exacerbating this affordability trend.

Particular sensitivity can be seen in first home buyers and younger families seeking to upgrade and increase house size. Conversely, banks are exhibiting preference for larger, pre-existing clients which demonstrate higher incomes and a known, pre-existing risk for the bank (as opposed to new and lesser perceived quality).

Australia’s housing market faces a tug-of-war between upward pressures driven by high immigration and constrained supply, and downward forces from stagnant (real) wages growth, tight lending conditions (for first home buyers/young family upgraders), a weakening set of dynamics for investment property (compounded by increased holding cost in State land taxes), and recent uncertainty surrounding Treasury reviews into negative gearing and the CGT discount. While the RBA’s pause on interest rates offers temporary relief, the true impact on house prices remains uncertain, with any future rate cuts likely to provide only modest support to a market contending with affordability constraints. As such, the near-term outlook points to flat or marginally declining real prices, with any significant recovery hinging on broader economic improvements and a more accommodative monetary environment in 2025.

Sourced from: