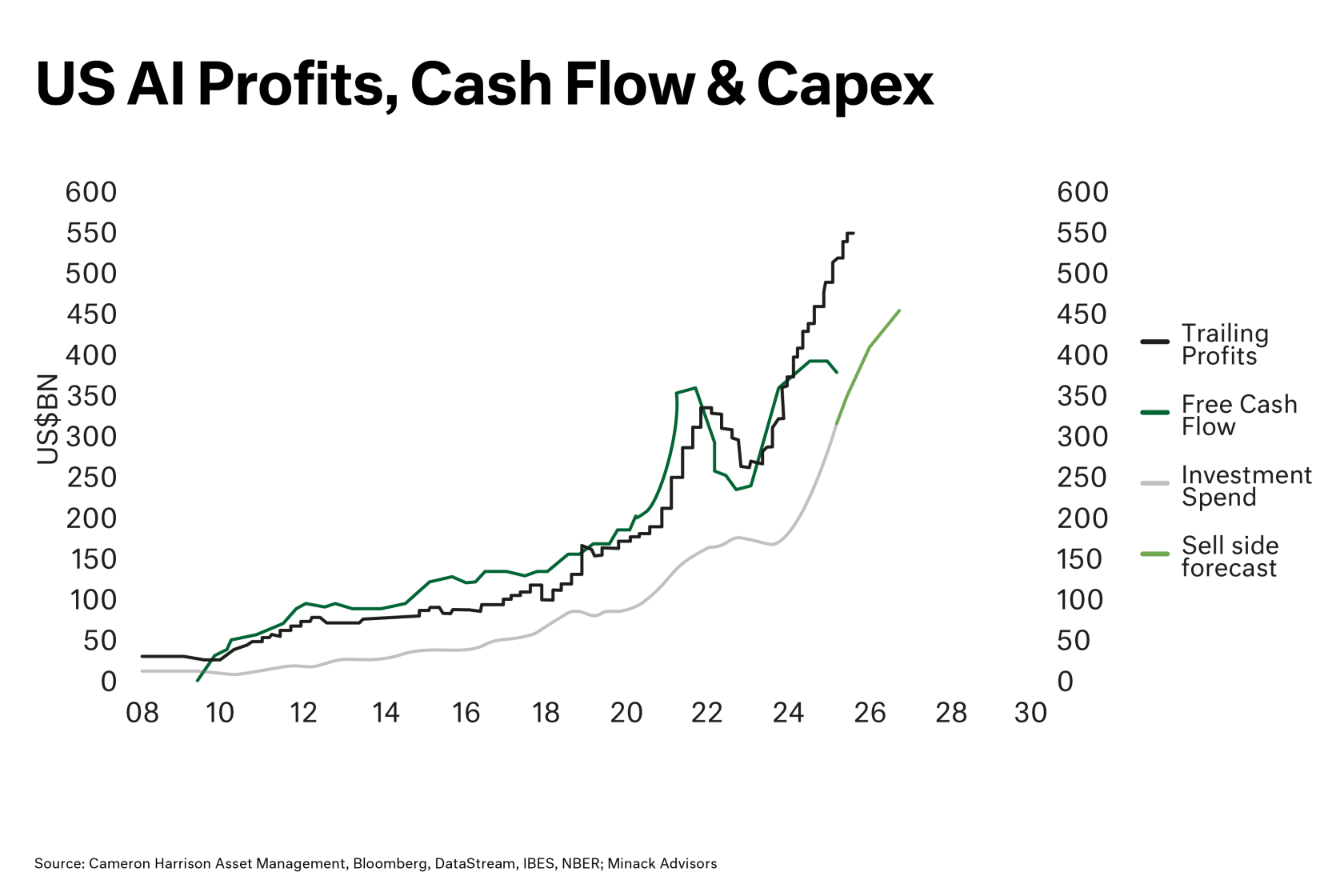

The analogies between the dot-com and telco bubble and today’s AI wave are striking. Valuations at record highs, a near-religious belief in technological transformation, and the promise of boundless future earnings have all been seen before. The parallels extend to the enormous capital intensity of this moment—massive investments into data centres, chips, and infrastructure—underpinned by an unquestioned conviction that AI will reshape every corner of the economy.

Yet the harder question is not whether this is a bubble, but how it ends. History—from tulips to railways to the dot-coms—suggests that technological revolutions often overshoot before finding equilibrium.