11 years and 6 months; that is the time that has passed since the last cash rate increase by the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA). The trigger for the about-face in policy direction has been the sharp rise in headline inflation numbers to 5.1% in the March quarter, and positions Australia in lockstep with its global counterparts.

However, Australia is not in the same position as other developed economies, where wage growth is rampant and driving domestic inflation pressures, and we expect a significant divergence in policy response over the coming 12-24 months that will see Australian rates rise slower than elsewhere.

We note the following drivers:

Offshore Driven Inflation: Australia’s current wave of inflation is due to external factors – Chinese production closures, supply chain / shipping costs, oil prices due to the Ukrainian conflict – and not (yet) due to rising wages. These are factors that are largely outside the control of the RBA and are expected to subside regardless of policy action.

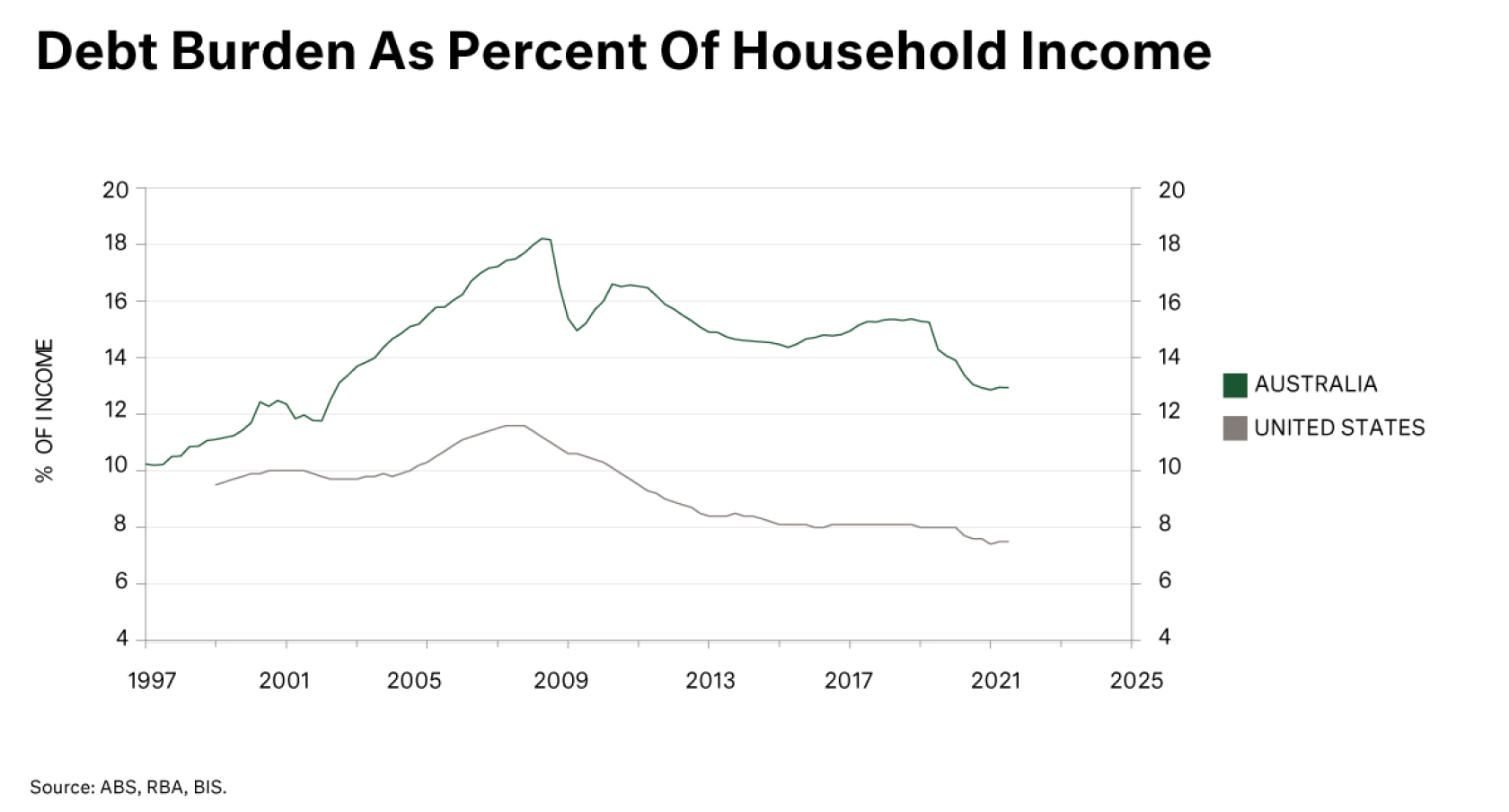

Higher Household Debt: Australian household debt is significantly higher than most other developed markets, a function of avoiding a GFC housing shakeout. High debt levels magnify the impact of interest rate increases, meaning the RBA can raise interest rates less to achieve the same tightening impact.

Variable Mortgages: Australian mortgages are predominately variable loans or fixed at less than five years. The US by contrast is predominately 15 to 30-year fixed rate mortgages. The variable nature of Australian debt means that any increase in rates impacts the entire stock of housing debt, not just new mortgages – this (again) magnifies the impact of RBA actions.

Higher Immigration = Lower Wage Growth: Australian Governments across Federal, State and Local Council levels are hooked on population related economic growth. Higher populations equate to higher GST revenue, higher stamp duty revenue, higher council rates revenue and higher income tax receipts. After two-years of low or no net immigration we expect to see a period of immigration catch-up, which will soften the impacts of current labour shortages and dampen wage growth.