The sustainability of public debt rests on four pillars: the primary fiscal balance (revenues minus non-interest spending), the real interest rate, real economic growth, and the level of existing debt. Particularly crucial is the relationship between real growth and real interest rates. When economic growth exceeds interest costs (g > r), governments can maintain deficits without exacerbating debt burdens. But when the equation reverses (r > g), as it has since 2023, debt trajectories become significantly more fragile.

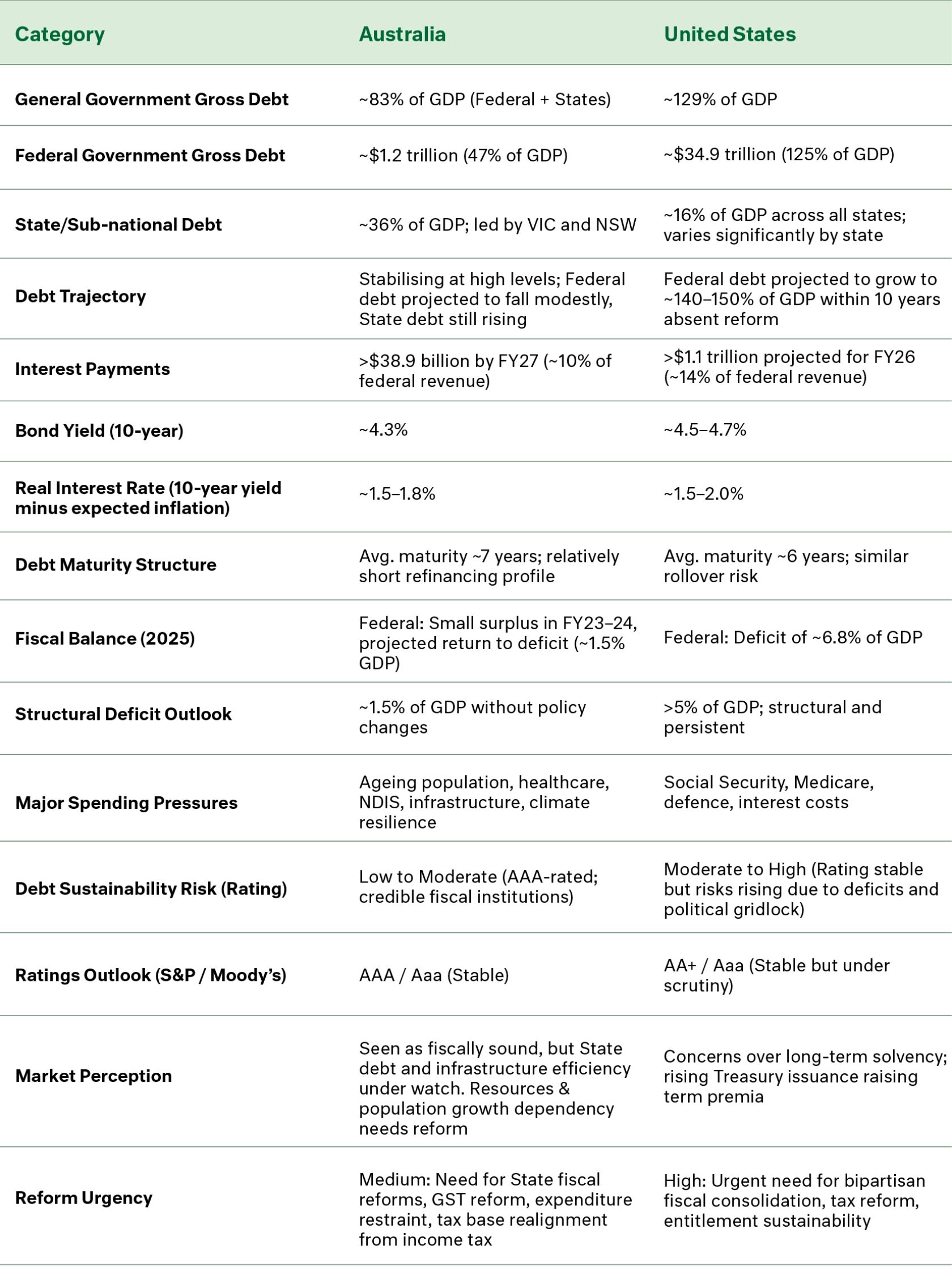

Australia’s gross public sector debt (including state debt) is expected to exceed 83% of GDP in 2025 - up from 41% pre-COVID. In the United States, debt is projected to reach 129% of GDP by 2025, with forecasts indicating 140–150% within a decade without substantial reform.

Leading financial institutions and economists have issued increasingly stark warnings.