The RBA may have lost its patience, but the Australian economy is not in the same place as the US. Interest rate normalisation will be much slower, longer, and lower than Mr. Market believes.

The US rate tightening cycle has begun in earnest with markets pencilling in at least another half-dozen rate rises in 2022. With wages growth in the US running at 5.8% year-on-year, we think that this may be a plausible, albeit slightly hawkish, forecast from Mr. Market.

This hawkishness has seeped into Australian bond market mindsets, and we caution against extrapolating the economic conditions in the US to Australia for 3 key reasons:

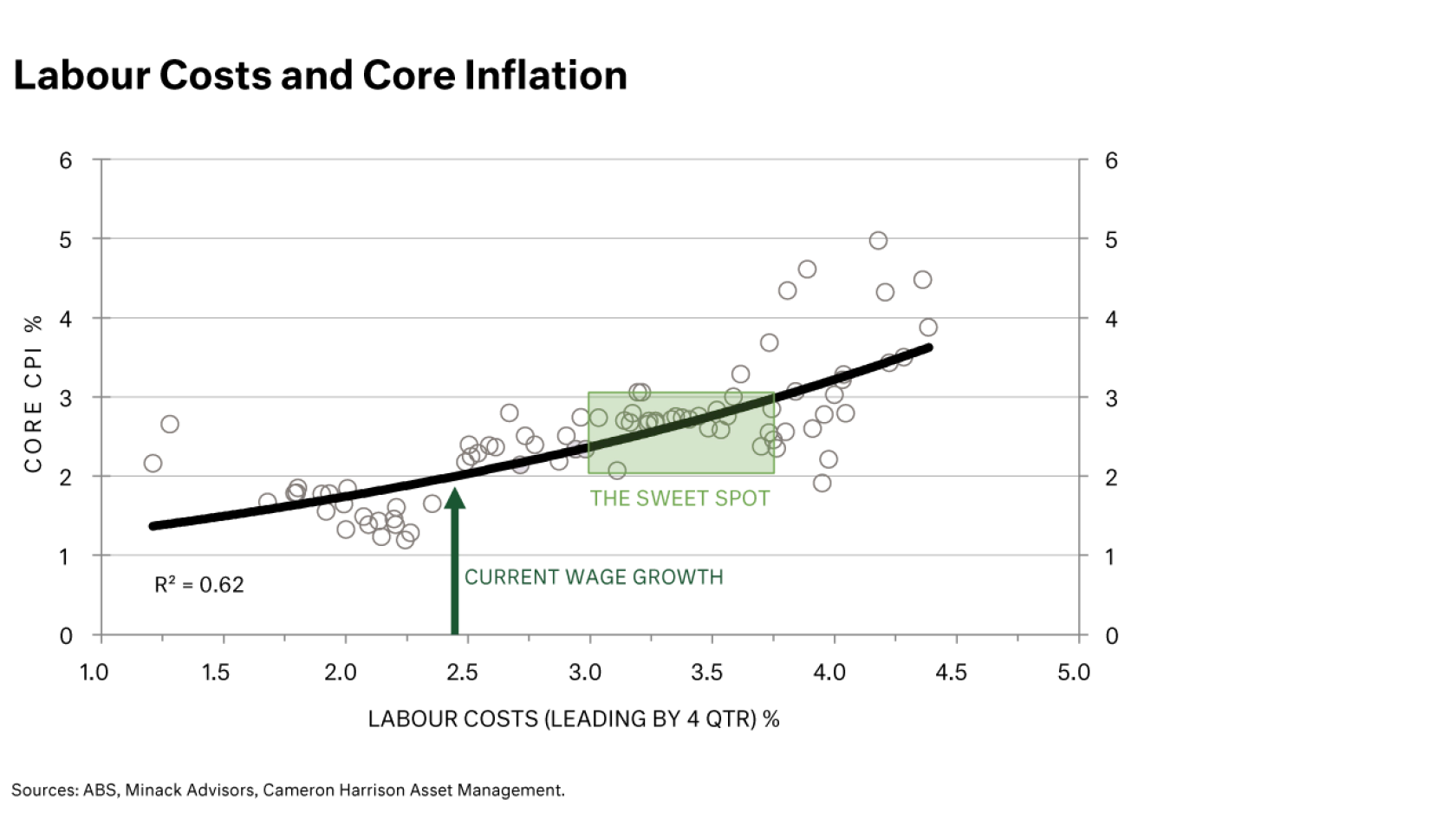

Australia does not yet have an issue with wages growth. The most recent data pointed to a 2.4% year-on year increase.

The slight uptick in wages that has occurred, and any increase that will follow, has been driven by the reduction in labour supply, with negative net migration over 2020 and 2021.

Net migration levels are certain to rise in the next few years, resolving the labour supply constraints that have marginally pushed up wages.

Watch the interview and read a 1-minute summary, below: