This article is a transcript of a webinar held by Cameron Harrison on 6th April 2022.

View the presentation here.

The post-GFC period was characterised by secular stagnation – a combination of low investment & consumption, excess saving, stagnant wages growth and ageing populations that results in low growth and deflationary pressure. An overreliance on monetary policy to stimulate economic activity, with fiscal policy hamstrung by austerity policies, led to ultralow interest rates, and strongly rising asset prices.

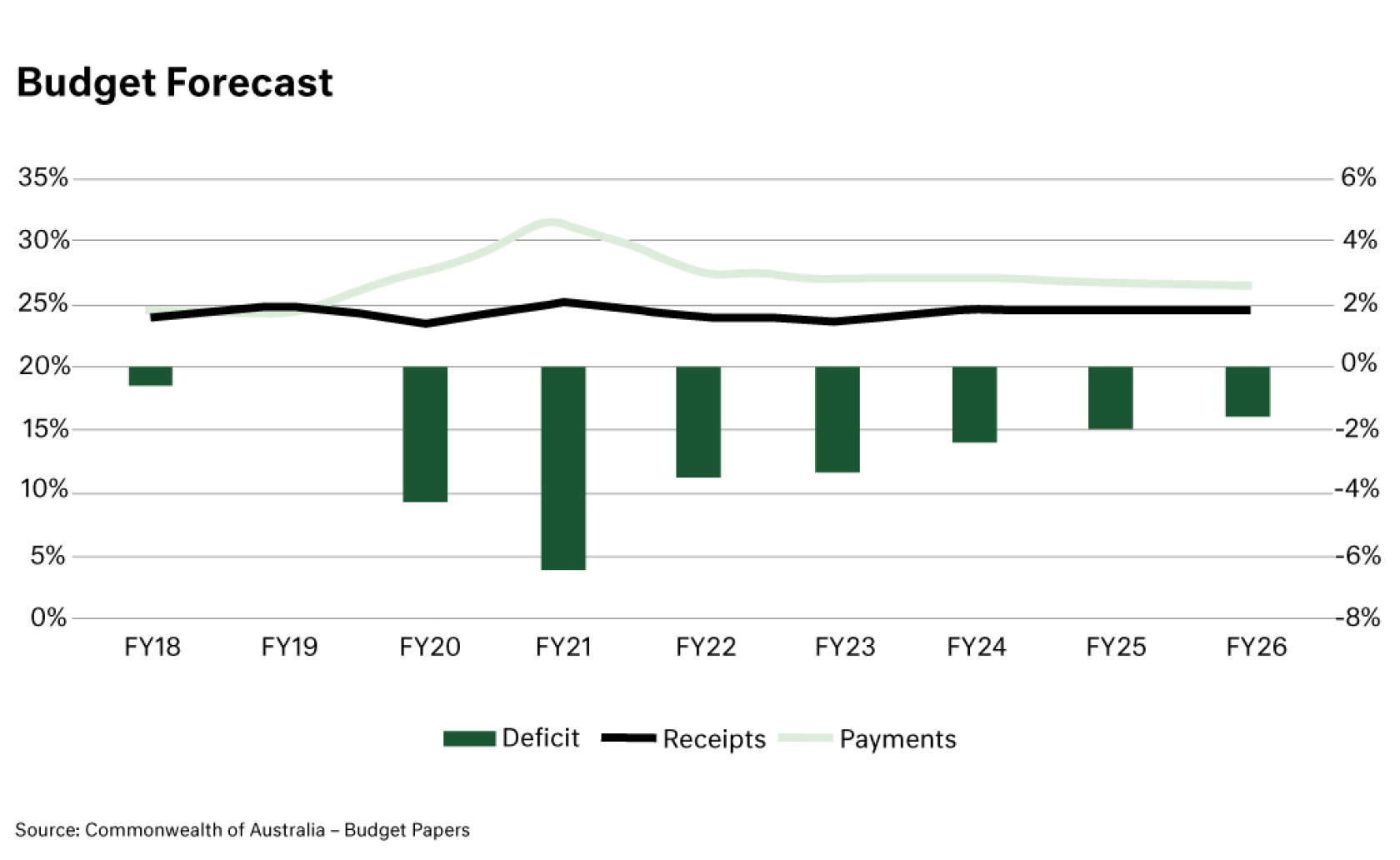

The onset of the pandemic heralded the re-emergence of significant expansionary fiscal spending. Domestically, this was in the form of the JobKeeper and JobSeeker packages, with similar packages deployed across most developed economies. These policies were highly effective at sheltering voters from the financial impacts of the recession, but appear destined to result in a grossly enlarged role for central governments.

As we emerge from the pandemic the geopolitical environment has deteriorated and the expectations of fiscal support portent to moral hazard in Western, liberal democracies. In this environment could secular stagnation make war for stagflation?

The pandemic has caused three significant shifts in economic conditions that push against the demographic trends that have driven secular stagnation over the past four decades.

Rediscovering Fiscal Policy: It is easy to increase spending, but history has shown that it is very difficult to reduce back to pre-crisis levels. This time is proving no different, with the supersized increase in government spending being especially difficult to contain.

Reactionary Central Banks: After a decade of constantly undershooting their inflation target by attempting to pre-empt higher inflation, central banks around the globe have changed to a reactionary approach that will ensure inflation overshoots.

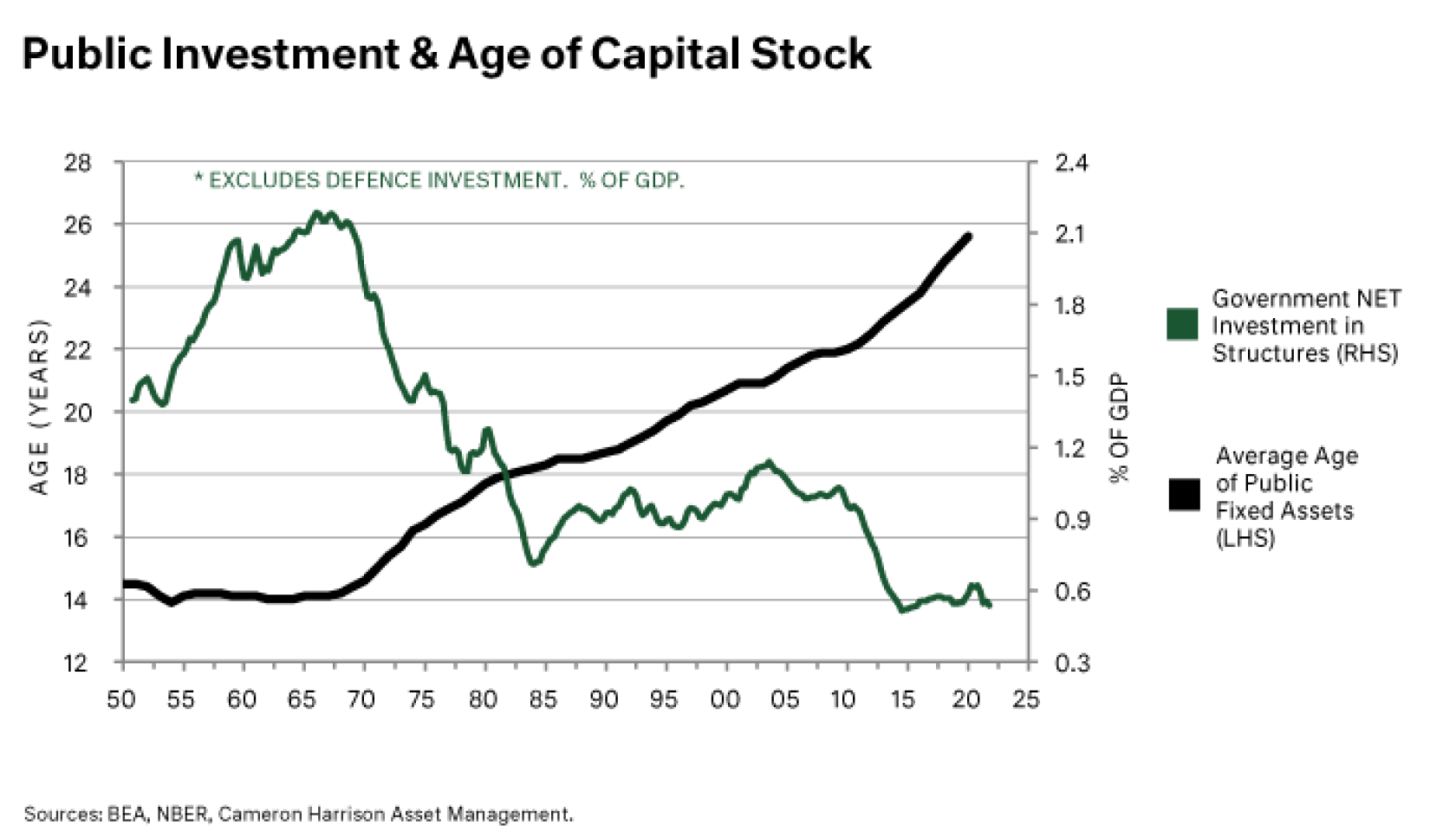

More Capex: Spending by corporates and governments will be higher over the next decade as they catch up after years of underspending on ageing infrastructure and defence capabilities are expanded in response to geopolitical tensions. On the energy front, forecasts estimate that $5 trillion in spending per annum is needed between now and 2030 to achieve net-zero by 2050.

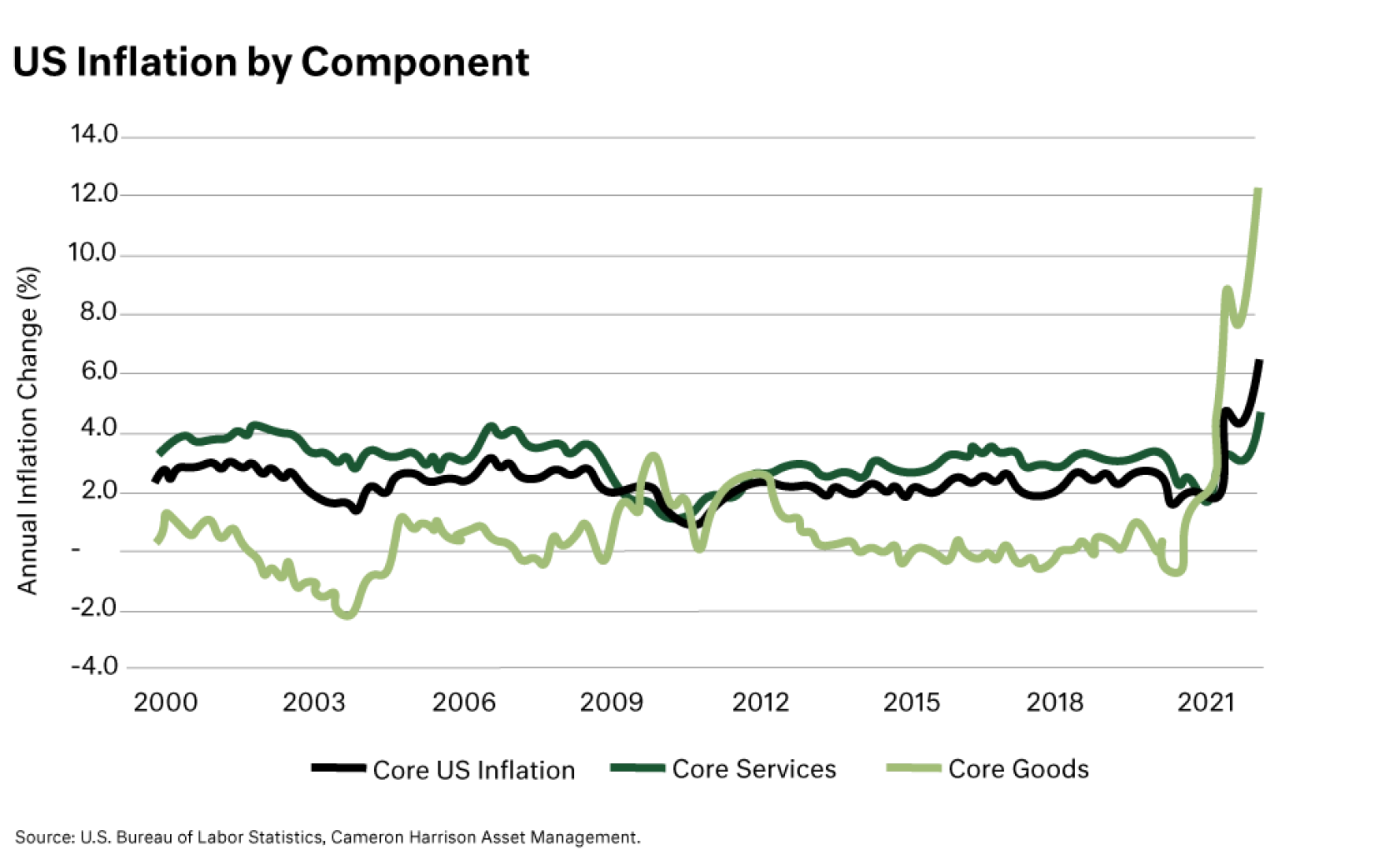

The US has an inflation problem. The initial wave of inflation resulting from the disruption to global supply chains is likely to dissipate in the coming year, but the real issue is the increase in shelter & service costs. This uplift is driven by a remarkable strong labour market that sees wages growth currently above 7% per annum. This level of growth is inconsistent with the US Federal Reserves’ inflation target and necessitates a sharp uplift in interest rates to maintain price control.

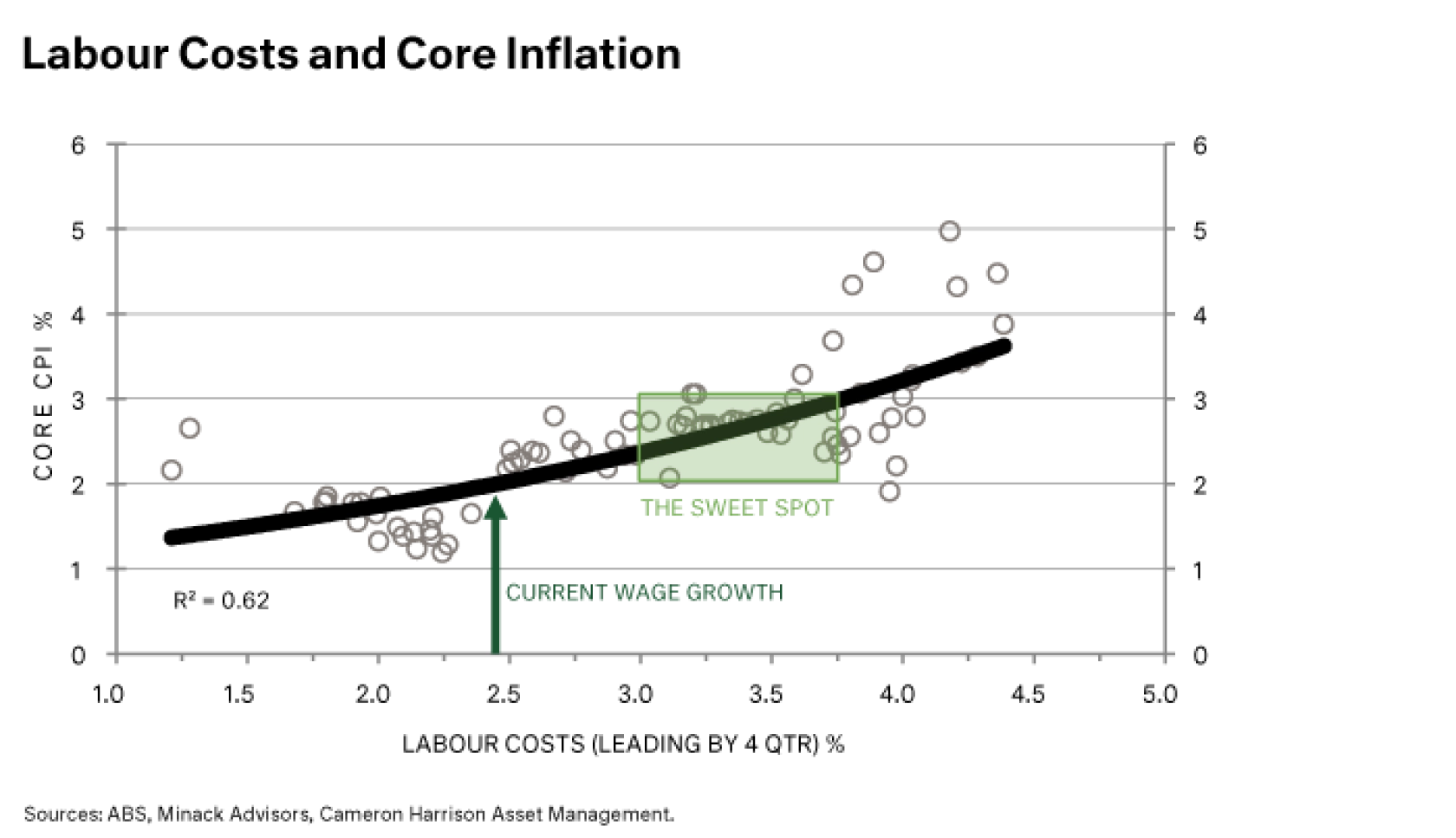

Australia does not yet have an inflation problem and may not have one. The RBA is unlikely to materially increase interest rates until wages growth is consistent with its inflation target of 2-3%. This implies that labour costs need to be sustainably growing at 3.0 - 3.75%; with the current growth rate lower than 2.5% this leaves significant breathing room for the RBA to wait and see.

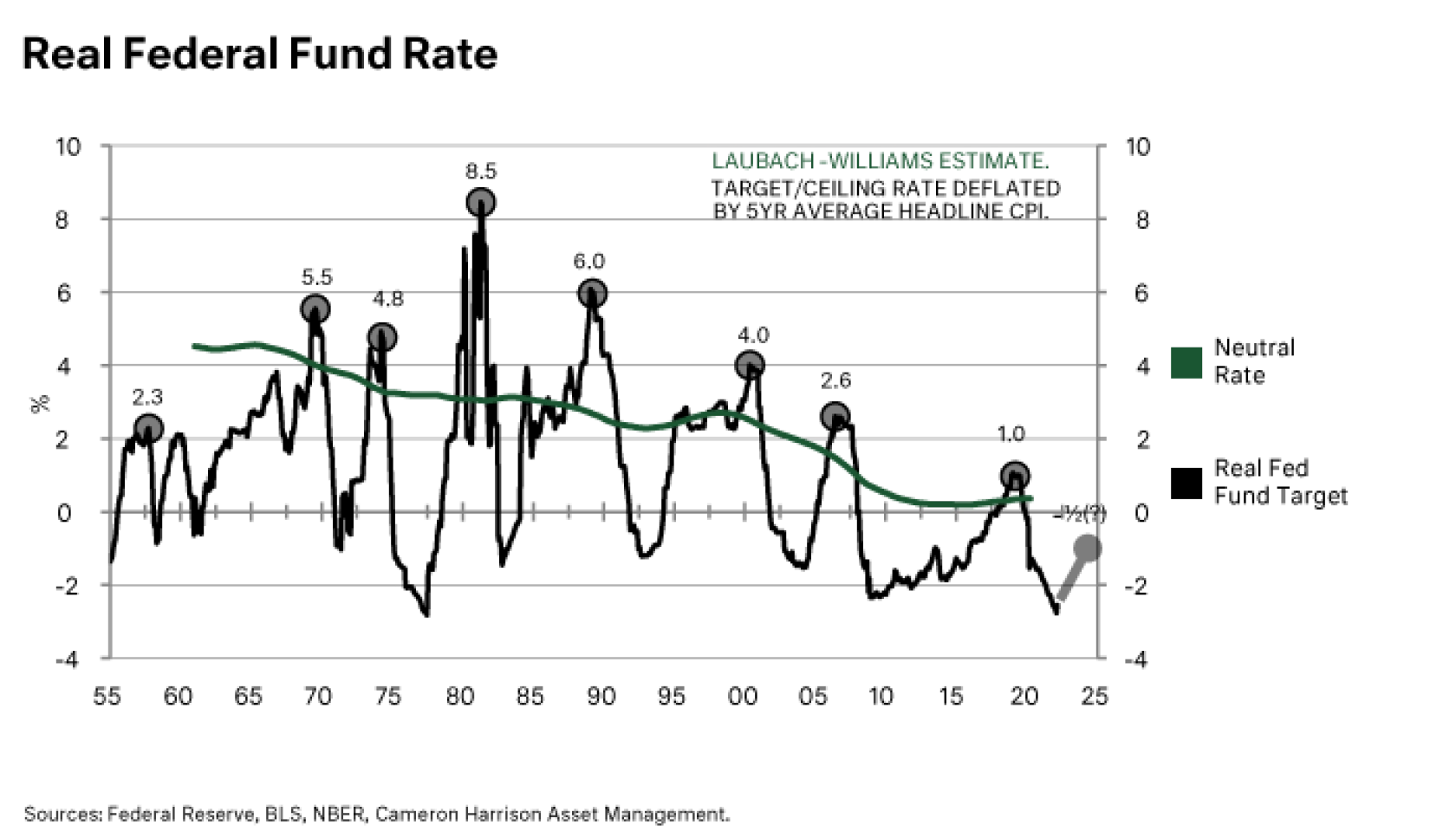

Markets are currently forecasting that real interest rates will peak at -0.5% in this cycle. This is consistent with the secular stagnation framework that persisted before the pandemic. Given the uplift in spending expected over the course of the next decade, it appears markets are underestimating how high rates will need to rise to crimp economic growth.

One of the key reasons why the US will be able to withstand higher interest rates is the health of the US consumer, with debt levels are at multi-decade lows after a period of deleveraging post-GFC and wages are growing strongly. As such, it seems likely that the cycle high for interest rates will reach close to or above 4% in nominal terms.

Given the rising rate environment, our Interest-Bearing portfolio in underweight Government and other high duration bonds, which will incur negative capital movements as rates increase. We are also concerned about global corporate credit. Nearly half the outstanding stock of corporate credit in the US was issued in the last 2 years and will need to be refinanced in the future into a less liquid market facing the trifecta of geopolitical uncertainty, higher interest rates and higher commodity prices.

On the flip side, we are overweight floating rate financial and corporate bonds. The return on floating rate bonds increases as interest rates go up and do not lose their capital value in the same way that fixed bonds do. As such we have seen the expected return on our strategy increase from under 3% near the end of 2021 to over 4.1%.

We also remain positive on residential mortgage-backed securities with seasoning pre-2021, that is mortgages that were issued either below or in the early stages of the pandemic and benefit from the uplift in capital values that have occurred over the past 18-months.

To have a widespread bear market in equities, this normally requires a recession. We believe that a recession is unlikely in the year ahead due to the large amounts of fiscal stimulus that are still working their way through the bank accounts of households and corporates.

In this environment, it appears likely that there will be a rotation away from previously fancied sectors – like communication services, loss-making, non-industrial technology – and towards cyclical sectors, like industrial metals, materials, and logistics. Companies in cyclical sectors can grow earnings faster than the wider economy.

We also maintain our overweight positions in health and agriculture, as both offer inflation defensive characteristics to the portfolio.

The key themes have been a flight to higher-quality office buildings or a shift to the city fringes. We think the office will regain most of its importance to the workforce and expect to see margins tighten. However, we are cautious on lower quality stock and prefer fringe CBD or industrial co-located office.

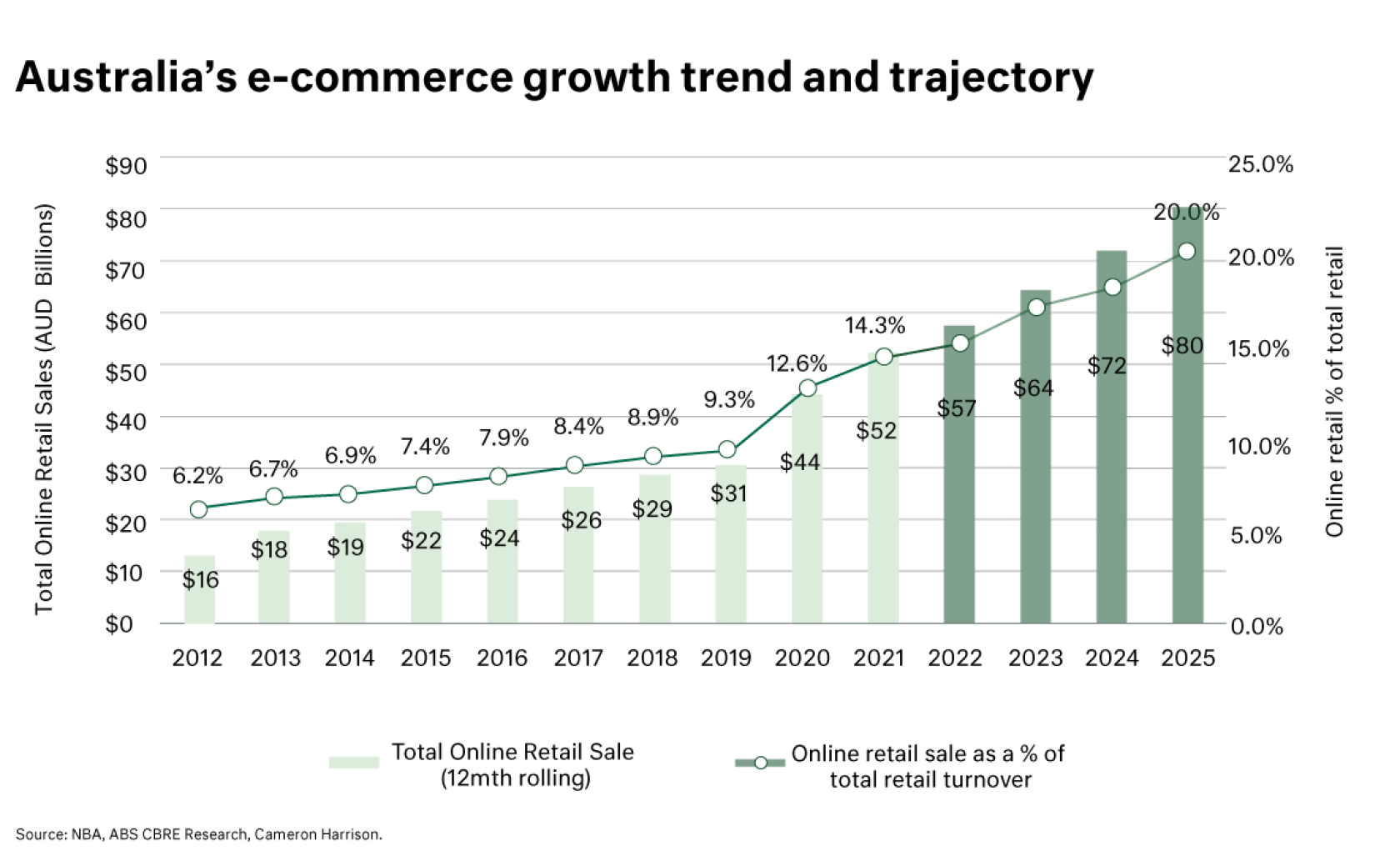

Industrial property should continue to benefit from additional demand as corporates resort to further onshoring of inventory to insulate their supply chains from disruptions. On the supply side, the cost of land and construction has jumped considerably, slowly the pipeline for new developments. The combined impact of this should see further tightening in yields.

In the retail market, the shift to online shopping is not something that we expect to unwind as it represented an acceleration of a pre-existing trend. Some sub-sectors will be immune to this in the short-term, supermarkets, chemists, and we have added to our investments in these areas. We continue to have no meaningful exposure to retail shopping centres.

Cameron Harrison have been advising business owners and their families on asset allocation and intergenerational wealth management for over 50 years. We have demonstrated over a long period our ability to manage investments through both the good times and bad by keeping the client at the centre of our business.

For more information on our approach to investment strategy or any other inquiries, please contact us at +613 9655 5000.

Sourced from: