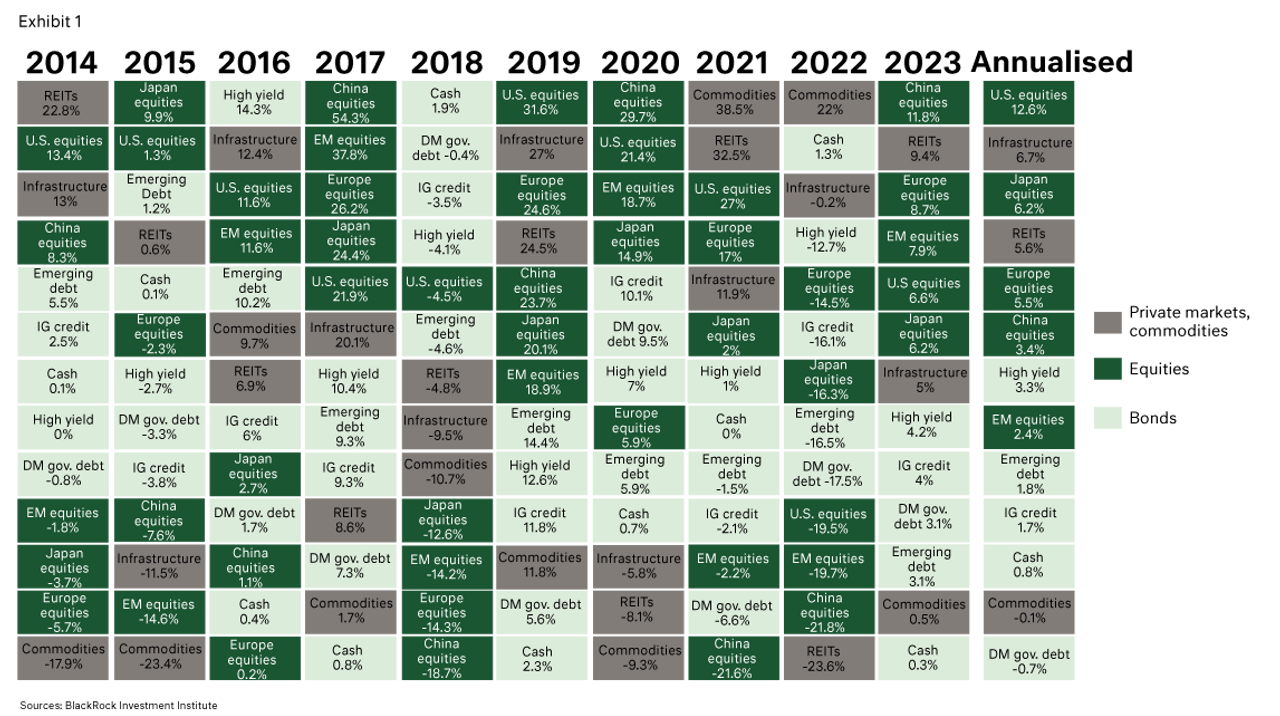

The performance of individual asset classes and by extension multi-asset class risk strategies in calendar year 2022 were uniformly the worst for nearly 15 years. This is illustrated in the heat map table below for the last ten years (exhibit 1). What this also illustrates is the significant variability of returns from one year to the next. Over a 10-year period, notwithstanding significant cross asset class performance variability, higher risk asset classes continue to perform better than bonds and cash. As we will discuss further on, a benign inflation environment has positively contributed to this outcome. Considered over 50 years, the asset class performance rankings are again quite similar, though the degree of outperformance of risk/growth assets is somewhat narrower, with bonds and cash producing acceptable returns.

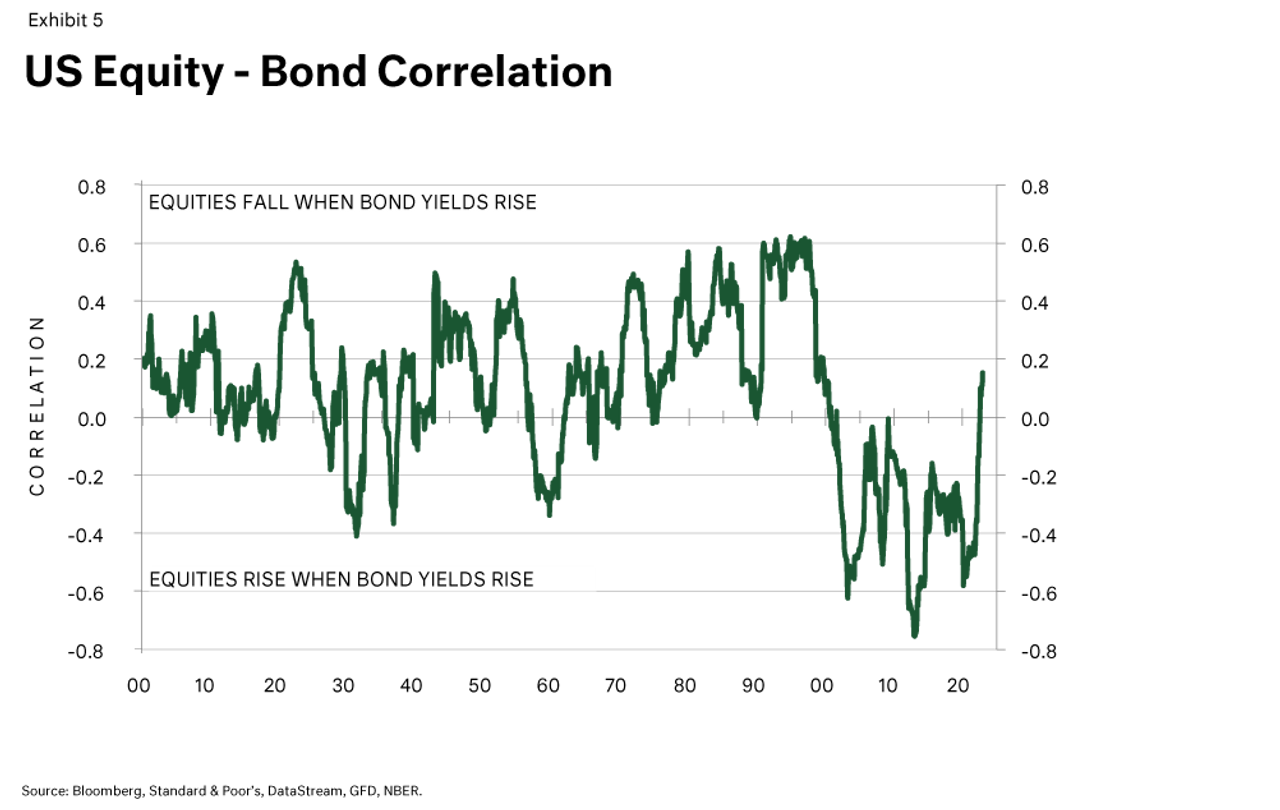

The returns for asset class in 2022 reflect positive correlation – that is, as equities performed poorly as a risk asset, so too did a portfolio of government bonds. This meant both equities and bonds were positively correlated. This is out of character for the last 20 years where the relationship has been one of more negative correlation (exhibit 2). What this meant is that when equities declined, bonds tended to perform better – bonds were a hedge to equity volatility and supported diversified returns. This has not always been the case. If we go back to the period from 1967 up to 1999, this relationship was broadly positively correlated.

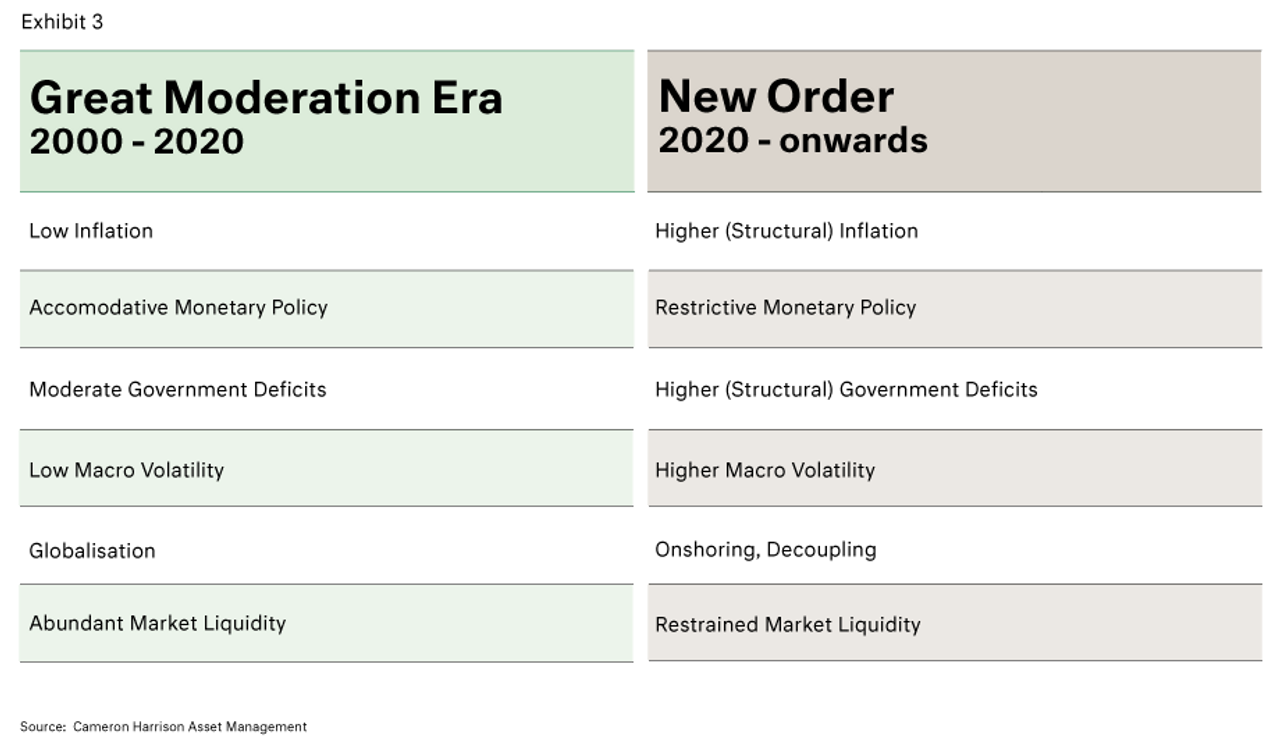

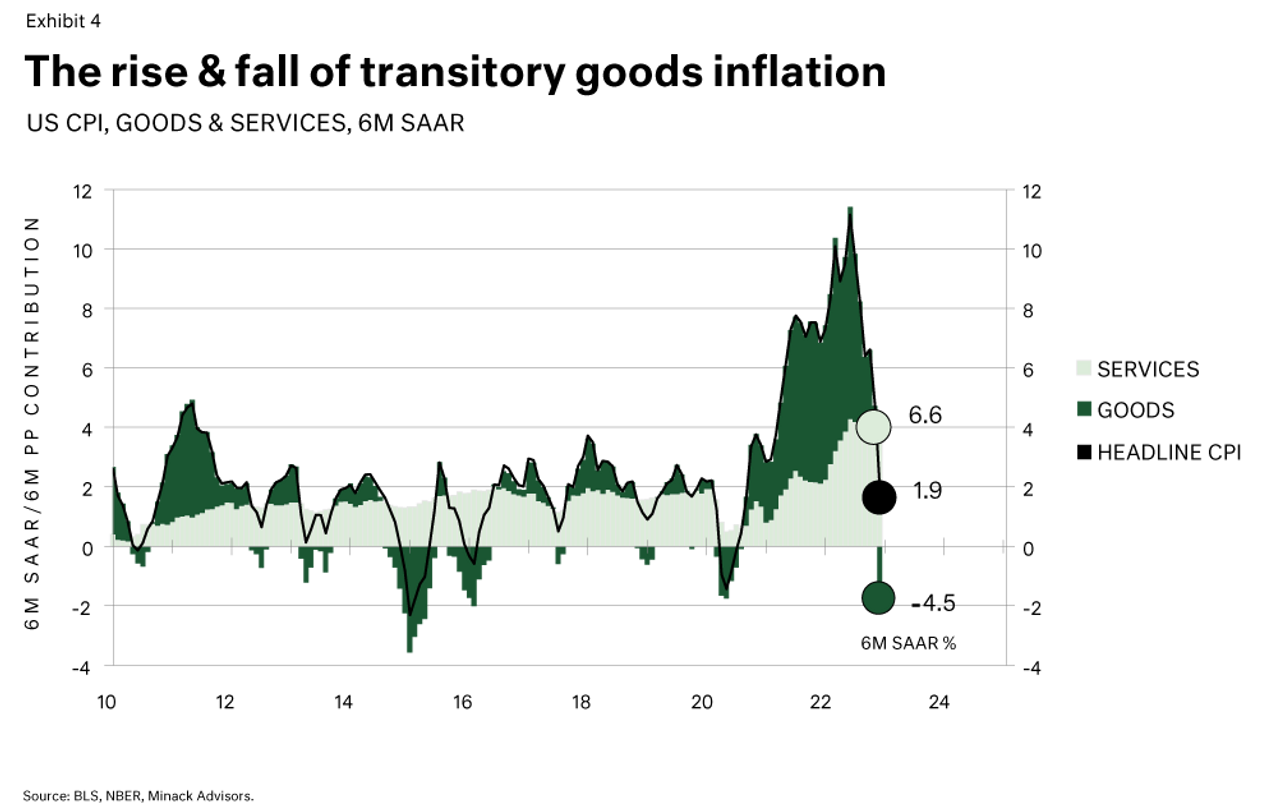

A key factor to the correlation relationship is the prevalence of inflation and inflation expectations. The period of 1967 to 1999 was marked by levels of higher inflation, whereas the period from 2000 to 2022 was a period of the ‘great (inflation) moderation’ and low and lower bond rates. In 2022, this assumption of forward-looking benign inflation and accompanying low bond rates was effectively destroyed. The resultant implications for asset allocation strategy moving forward are significant.

The economic and financial environment as we were (2000-2022), and now, how we see it looking going forward is outlined in exhibit 3. The go-forward position has the hallmarks of increased regulation, increased government involvement through policy discretion (social, energy transition, pricing in the market) and automatic involvements (ageing: health & pension). This risks an environment of more rigidity, less efficient capital allocation, lower productivity, lower real growth and higher unemployment and inflation. A key point we note is the need for asset allocation to be dynamic in its approach. In this regard, we have been operating our Core Dynamic Multi Asset Allocation Strategy since 1993.

In the US and Australia, we see a significant risk that central banks overtighten interest rates and cause meaningful recession (as compared to an otherwise mild recession). This then potentially creates a tussle between taming inflation (central banks) versus the political costs of recession. In this regard, central banks should co-ordinate with the actions of government. It is not just consumers who need to reduce demand pressure, but so to does government, yet central banks for all their independence, are loathed or paralysed to state this to their political masters.

The risk of recession in Australia is becoming more pronounced as the RBA struggles with its forward looking analysis, indicators and how to conduct policy – this leaves the ‘bludgeon’ approach which will work, but at considerably more cost and damage to the economy. It is the symmetrical approach to COVID where the RBA gave, underwrote and promised everything, so now the symetrical opposite. As a consequence, the forward rhetoric of the RBA, if delivered, would ensure a (material) recession which we consider unnecessary (but likely). In the US, the equation is one of delivering lower employment levels (ie. unemployment) with consequential lower wages growth pressuring services inflation. The risk here is likewise of over tightening and recession. In the US however, the potential damage to overtightening is lower given the relative lower level of household indebtedness and good wages growth for lower to middle income earners. Add to this the general good balance sheet health of US corporates.

We do think inflation significantly moderates from its current elevated levels, but will prove more persistent and will not return consistely to the levels witnessed over the Great Moderation period (2000-2020). As we noted earlier, monetary policy and fiscal policy has not been able to synchronise for a long period of time, apart from the extraordinary efforts under crisis conditions such as through COVID and the GFC. With governments adding to inflation through high spending as a proportion of the economy, that only leaves central banks leaning on aggregate demand and ‘jaw-boning’ consumers, but they also need to ‘jaw-bone’ government.

Whether inflation is tamed or crushed, the cost will be borne by households through wealth destruction and contraction in household spending. This in turn harms businesses exposed to private consumption (it being over 60% of GDP) and the housing sector. One should expect that corporate earnings will decline over 2023 with some offset to valuation through ultimately moderating 10 year bond yields and in Australia, robust national income through a high terms of trade.

There is now healthy income for fixed income securities after an “income drought” for the last 12 years. We view that this provides some opportunities in specific duration exposures.

We remain positive on short to medium term credit issuance across quality issure such as banks, quality corporates who re-financed debt at low rates and some government agency debt. Long-term governments bonds (10 years+) we think suffer in the new positive correlation environment and hence provide minimal or no benefit when equity markets fall. This is compounded by governments future funding needs continuing to expand to meet ageing related spending (health, pensions) and increasing array of other social programs (NDIS). This we think this requires higher yields to compensate for term risk and higher likely inflation.

We also find attractive other “like” mid-duration assets. For example, well capitalised public commercial property with weighted average lease expiry of at least 5 years provides a healthy, indexed yield and capital base. This is against the backdrop of private commercial property prices yet to fully absorb adverse 10-year bond rate movements.

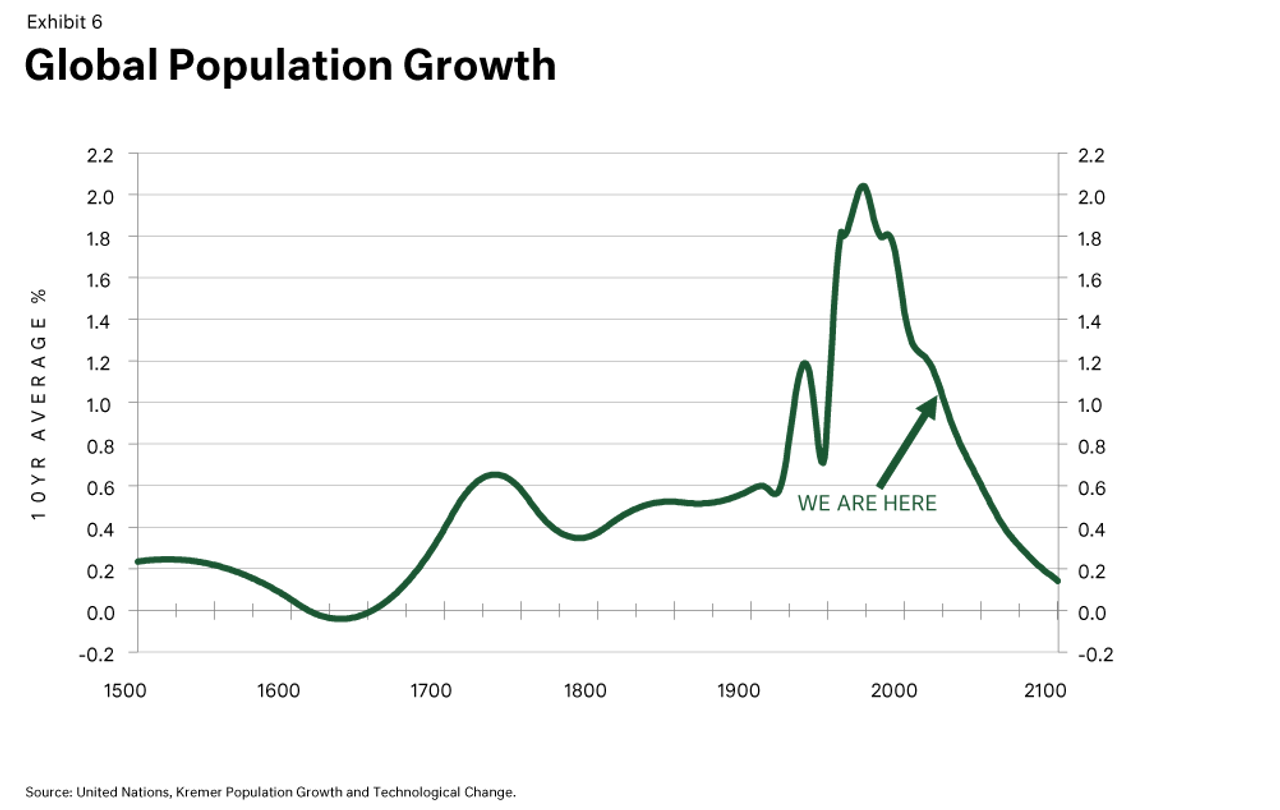

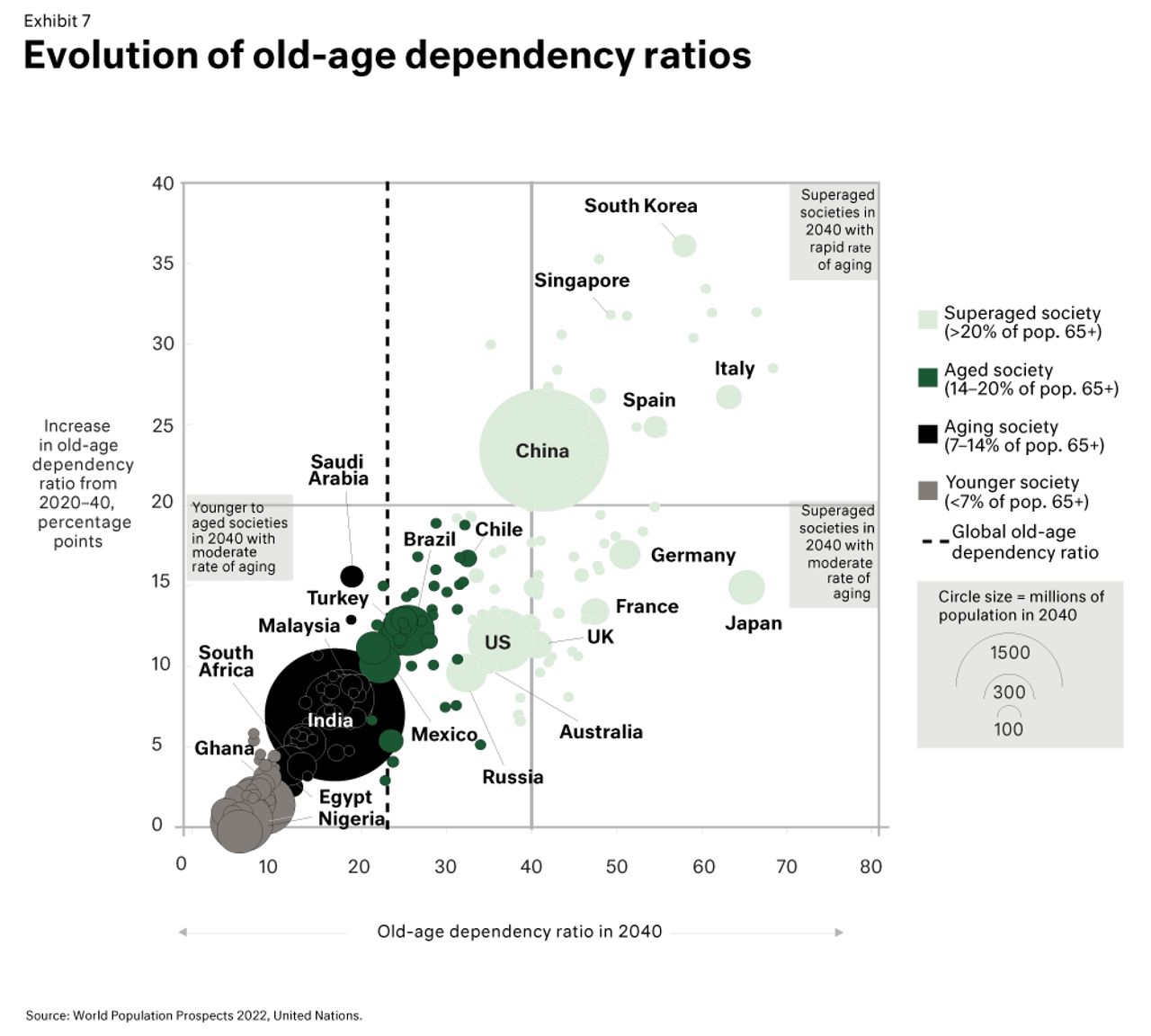

There is and will be a constant theme prevailing over asset allocation strategy for a very long time to come, and that is ageing. The rate of global population growth is in sharp decline (and has been for some time) and is expected to continue to do so (exhibit 5). When combined with an ageing population, this sees many leading economies become ‘super-aged’ where over 20% of their population is 65 years of age or more (exhibit 6).

There are many issues and implications that ‘super-aged’ countries are faced with, such as:

Government’s role in developing and supporting policy that acknowledges this old-age dependency and encourages healthy ageing, through:

Workplace flexibility to have older workers remain connected to the workforce, thus benefiting their wellbeing and broader economic outcomes – this requires a fit for purpose retirement incomes policy.

Healthcare which operates with a clear understanding of what constitutes and assists healthy ageing.

Government spending and taxing policy needs to reconcile between those working, paying tax and the funding of old-age programs such as health care and the old age pension.

Understanding the economic consequences of significant private savings, higher government expenditures and reduced demand from a smaller working age population.

Geopolitical tension occasioned by the US and China’s ‘super-ageing’ compared with modest Indian and African continent ageing.

Our approach to asset allocation advice and structuring over 30 years, seeks to carefully align wealth and investment strategy objectives with achieving balance in the delivery of real growth in income and capital. Depending on your risk view, investment horizon and specific factors such as volatility, currency, inflation and specific funding requirements, we can provide either our core spectrum of asset allocations or client bespoke asset allocation.

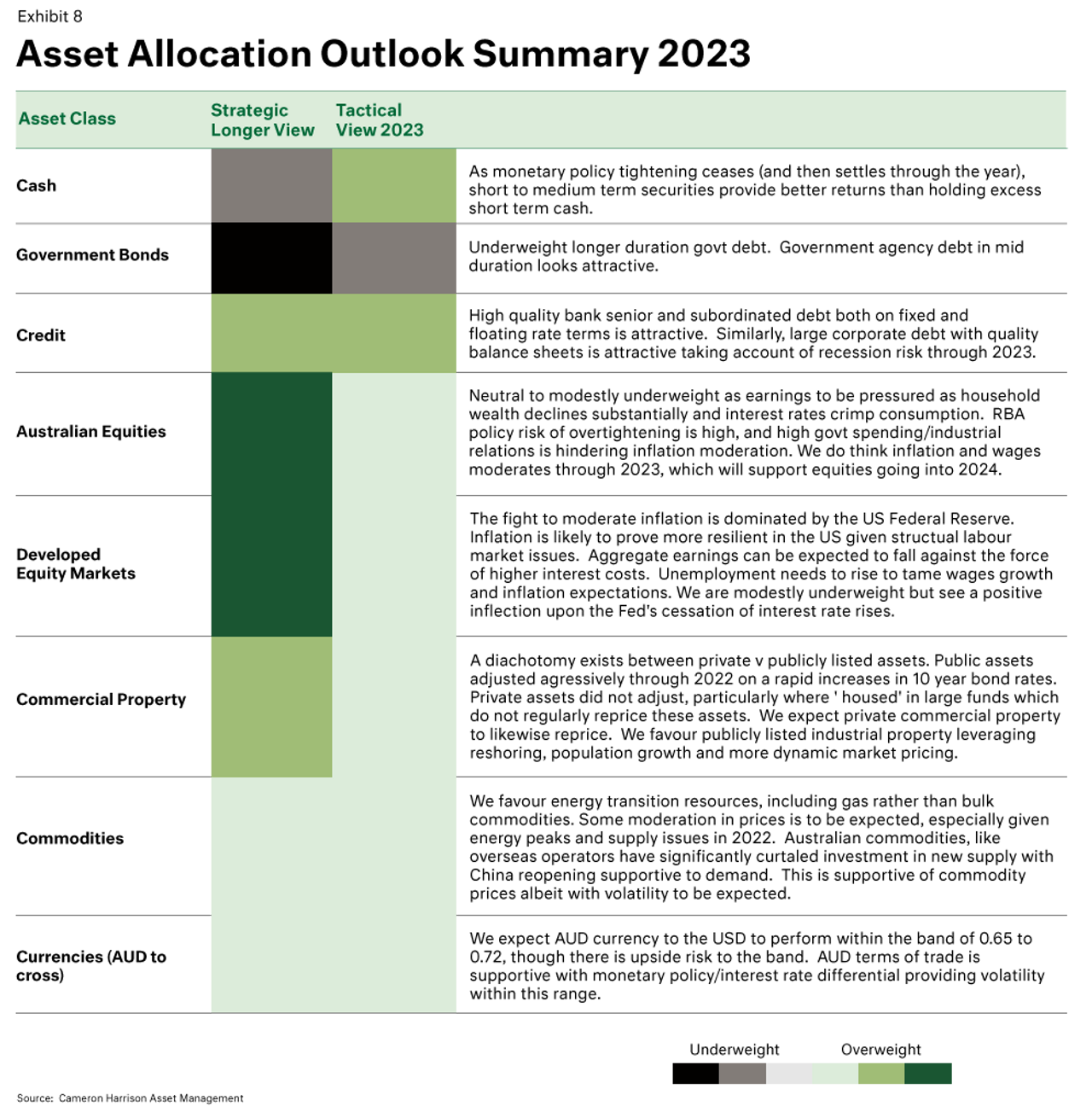

Our strategic (long term) and tactical (2023) asset allocation positioning is shown below. It shows our relative positioning which in turn, depending on your designated strategy, is reflected in an adjustment upwards or downwards.

Cameron Harrison have been advising business owners, families and significant wealth investors on asset allocation and intergenerational wealth management for over 50 years. We have demonstrated over a long period our ability to manage investments through many economic cycles, both through the good times and bad, by keeping the client at the centre of our business.

For more information on our approach to asset allocation and investment strategy or any other inquiries, please contact us on +613 9655 5000 to discuss with one of our Partners or contact our us here.